When Work Became Mechanical

The Industrial Revolution and the second rung of abstraction

The farmer from last week—the one who planted those seeds and began to live in the future—he’s leaving.

The tractor arrived at his neighbor’s farm, then the mechanical thresher, then the combine. Machines that could do the work of ten men.

Farms were getting bigger, more efficient, more mechanized. There wasn’t enough work anymore.

But the cities, he’d heard there was work in the cities. Good wages. Steady work.

So he goes.

He used to walk behind the plow, hands on the wooden handles, feeling the blade catch on rocks, sensing when the soil was too wet or too dry.

He used to swing the scythe in rhythm with his breath, feeling the grain give way, hearing the particular sound of ripe wheat. His hands knew the land, his body moved with the seasons.

Now he stands still in the middle of a textile factory. The air smells of oil and cotton dust.

Twelve hours a day. Six days a week. His hands feed thread into a machine. The same motion, over and over.

The machine pulls the thread through mechanical wheels, under tension he doesn’t control, at speeds he doesn’t set.

Somewhere down the line—he saw it once—the threads become cloth. But he never touches the weave. Never feels the texture. Never sees the pattern.

The machine makes it, the same weave, the same way, every time. He doesn’t decide anything. He just keeps it running.

Last week, we explored how agriculture taught us to live in the future. How planting seeds created the first great cognitive shift from immediate to delayed return. The farmer learned to think in seasons, to delay gratification, to hope that effort today would yield results months from now.

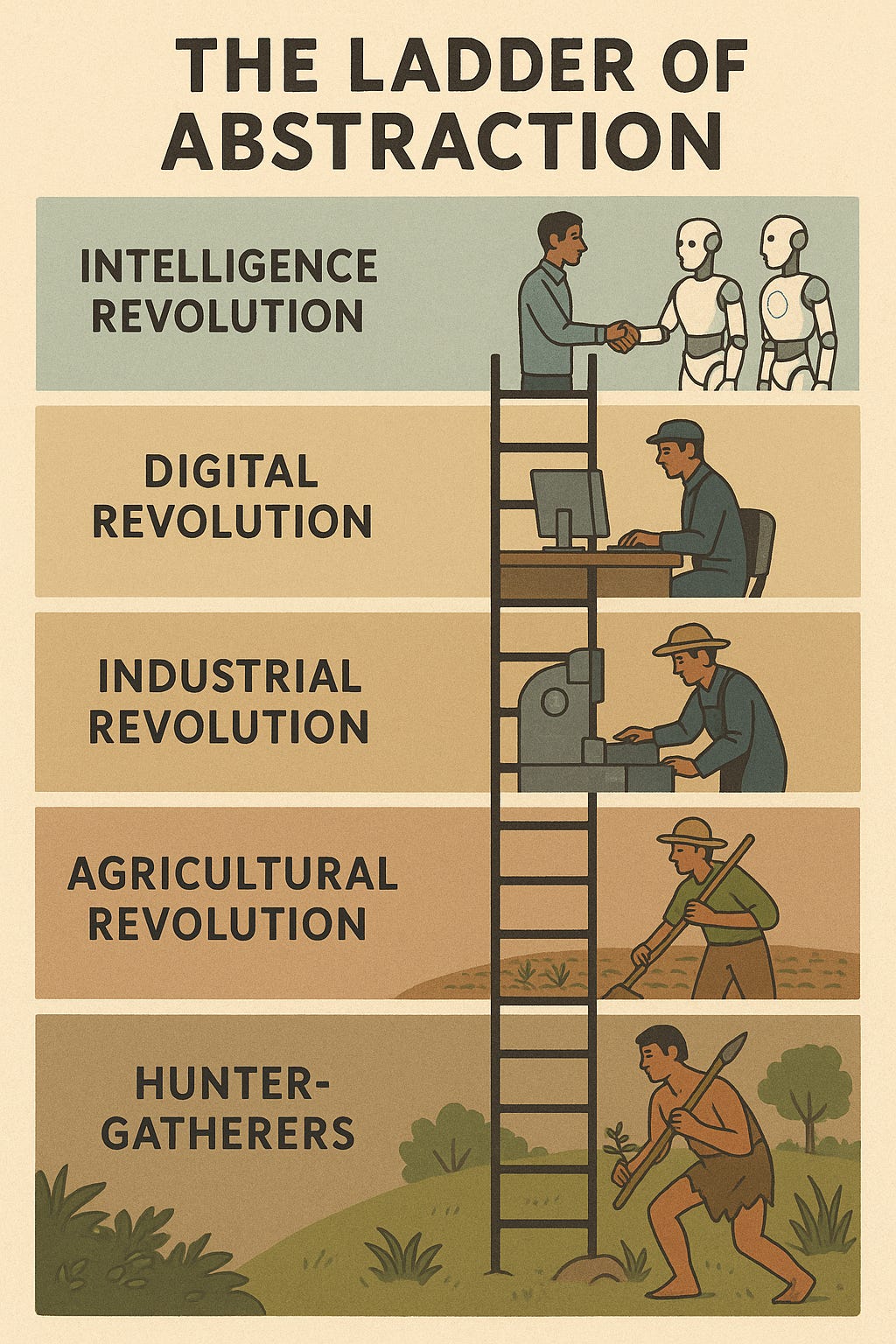

That was the first rung on the ladder.

But even after agriculture, something crucial remained: his body still touched the world.

Then came the machines.

The Three Severances

The Industrial Revolution didn’t just mechanize production. It severed three fundamental connections that had anchored human cognition to the present moment for millennia. And unlike agriculture—which first pulled our minds into the future but left our bodies grounded—industrialization removed the ground entirely.

First Severance: From Embodied Work

Consider what factory work actually required.

Repetitive, deskilled labor. You didn’t need to feel anything. The machine determined the rhythm, the pressure, the outcome. Your hands became servants to mechanical timing, not interpreters of material reality.

No embodied feedback. You couldn’t feel when something was “right.” The machine either worked or it didn’t. Your somatic intelligence—all those years of hands learning to read material—became irrelevant.

Mechanical intermediation. The machine stood between you and the thing you were making. You pulled a lever. The machine made the cut. The cause-effect loop that used to run through your body now ran through steel and gears.

And perhaps most profoundly: clock time. Time itself became mechanical. Fragmented into standardized units, sold by the hour, enforced by factory bells. Not sunrise to sunset. Not seasonal rhythms. Just mechanical increments—the same in winter darkness as summer light. Time became something you “spent” or “saved,” a commodity as abstract as currency.

Industrial psychologist Frederick Winslow Taylor would later make this explicit in his “scientific management”: workers aren’t supposed to think, just follow the system. But the irony is that living in this system requires constant abstract thinking—you just don’t think about what you’re doing. You think about what might happen, what others think, how you compare, whether you’ll have enough, whether you’re falling behind.

Your mind in the future, your body doing nothing that feels real.

Second Severance: From Natural Environments

But the Industrial Revolution didn’t just change work. It was the birth of modern cities. And cities created a cognitive environment that made our innate capability for present-moment awareness nearly impossible.

For the first time in human history, masses of people lived entirely removed from natural environments. Not occasionally indoors—agriculture still meant working fields, tending animals, tracking weather. But permanently indoors. Factory to tenement to street, all built environment, all human symbols, all the time.

Here’s what environmental psychology research reveals about what this does to cognition:

The Biophilia Hypothesis (E.O. Wilson): Humans have an innate need for connection with natural systems. We evolved in natural environments. Our nervous systems expect them.

Attention Restoration Theory (Kaplan & Kaplan): Natural environments restore directed attention—the effortful focus required by modern life. Without nature exposure, our attentional systems become depleted. We live in a state of chronic cognitive fatigue.

Generalized Unsafety Theory of Stress (GUTS): When we don’t see, hear, or feel nature, our default response is stress. Our nervous system reads the absence of natural cues as potential danger.

Think about what this means for our farmer in 1850:

Wake in a tenement. No sunlight. Walk streets crowded with people, horses, commerce. Enter a factory. Stand at a machine for twelve hours under gas light. Return to the tenement through fog and coal smoke. Sleep. Repeat.

No trees. No birds. No horizon. No stars. Nothing that evolved with human cognition for hundreds of thousands of years. Just bricks, machines, crowds, symbols, noise.

His nervous system never gets the signal that he’s safe, that he can relax. He’s constantly scanning for threats, real and imagined. The GUTS theory suggests this isn’t just uncomfortable—it fundamentally alters baseline cognitive functioning. He’s trapped in abstract processing because his environment provides no concrete, natural feedback to anchor to.

Third Severance: From Local Information

And there’s one more dimension: information from afar.

Mass printing meant newspapers. Newspapers meant knowledge of distant events. Suddenly his mind isn’t just tracking his field and his village—he’s processing information about wars in other countries, economic shifts across continents, social movements in distant cities.

This is abstract information. It requires abstract processing. He can’t see it, touch it, verify it directly. He lives in a web of symbols representing things happening elsewhere, to people he’ll never meet, in contexts he can’t directly experience.

Social comparison—which for 95% of human history meant comparing yourself to perhaps 50 people you knew intimately—now means comparing yourself to urban hierarchies of thousands, stratified by abstract markers: wealth, status, class, fashion, reputation.

Even his self-concept becomes abstract. His worth measured by symbols, not by direct relationship or embodied capability.

The Cascade

Here’s what makes the Industrial Revolution so cognitively transformative: these three severances don’t just add up. They multiply.

Let’s trace what compounds:

Rung 1 (Agriculture): Your mind lives in the future, but your body stays grounded through embodied work and natural environments.

Rung 2 (Industrialization): Your mind lives in the future AND:

Your body does nothing that provides real feedback

You live in built environments that prevent presence

You process abstract information about distant events

Your time is mechanized

Your worth is measured by symbols

Your nervous system is in chronic stress

Each element reinforces the others.

The machine deskills your hands, which makes you rely more on abstract thought. The urban environment stresses your nervous system, which depletes attentional resources. The clock fragments your natural rhythms. The newspapers fill your mind with concerns you can’t act on. The chronic stress makes it harder to stay present. The lack of embodied feedback makes it harder to trust your own judgment.

And here’s the rub: this cognitive style becomes mandatory for survival.

You can’t opt out. You must learn to live in your head, processing abstract information, following mechanical time, comparing yourself to invisible others, worrying about events you can’t influence. The environment demands it.

The mind becomes chronically abstract because the environment provides nothing concrete to hold onto.

This is the second rung of abstraction: We learned to live not just mentally ahead of ourselves, but physically disconnected from what we were doing, perpetually removed from natural feedback, constantly processing information about places we’ll never go.

What Was Gained, What Was Lost

This is where the story gets complicated.

This is not a judgment on the Industrial Revolution. It created the material foundation for nearly everything we value about modern life. Medicine. Education. Art. Science. The ability to solve problems at scales that craftspeople could never address alone.

We gained unprecedented abundance, lifted millions from subsistence, built the specialization that makes civilization possible.

But here’s what we need to sit with: every gain came with a specific cognitive cost. And we are only now, 250 years later, beginning to realize the extent of this.

We didn’t just change how we made things. We changed what it felt like to be human.

And this matters—not because we should return to pre-industrial life (we can’t, and I’m guessing you wouldn’t want to)—but because understanding the trade-offs is the first step toward reclaiming what was lost while keeping what was gained.

The Ladder Climbs Higher

Agriculture taught us to live in the future. Industrialization taught us to live in in the future inside mechanical systems—abstract roles in mechanical processes we don’t control, in environments that provide no natural feedback, processing information about worlds we can’t touch.

The farmer at the beginning of this article lost more than a job. He lost a way of being that kept him tethered to embodied reality, even in a delayed-return world.

We’re two rungs up now. Our minds are in the future. Our bodies are disconnected. Our environments provide no rest. We process information about things we can’t see or influence. We measure our worth by abstract symbols.

And we haven’t even gotten to screens yet.

Next Wednesday, we explore the Digital Revolution: when reality itself becomes optional, when information begins to divorce from matter entirely, when the screen becomes the primary interface through which we experience life.

Understanding how we got here isn’t nostalgia for a past we can’t return to.

It’s diagnosis.

We can’t address what we don’t see. And what the Industrial Revolution makes clear is this: abstraction compounds.

Each layer makes presence harder, not just different. Each rung makes it more difficult to feel grounded, embodied, alive.

But the story isn’t over. We’re living it now.

And understanding how we climbed the ladder is the first step toward learning how to move up and down it with intention.

See you next week.

—James

Note on AI collaboration: The ALIVE Letter explores how humans can stay fully human while learning to work with modern technology. In that same spirit, I collaborate with AI in the creation of these essays. As an industrial/organizational psychologist who studies human-AI collaboration, I carefully guide, refine, and evaluate AI outputs. At its best, this partnership helps me more clearly and authentically communicate my own thoughts and perspective than I am able to alone.

Love this perspective; the line 'The machine pulls the thread through mechanical wheels, under tension he doesn’t control, at speeds he doesn’t set' vividly illustrates the profound shift in agency from human to mechanism, a dynamic so relevant to understanding automation today.

Brilliant as always. I love how you’ve made the abstract easy to digest. Quite the feat of meta-cognition :) I look forward to next week!