When Reality Moved Behind Screens

The Digital Revolution and the third rung of abstraction

Part 3 of The Ladder of Abstraction series

We’re three weeks into a story about how human cognition has been progressively pulled away from direct experience and into abstraction. If you’re just joining us, here’s where we are:

Abstraction means living in your head instead of in direct contact with reality. It’s thinking about things rather than experiencing them. Planning future scenarios rather than being present to what’s actually happening. Processing concepts rather than processing sensory information.

This isn’t inherently bad—abstract thinking is what lets us plan, create, build technology and civilization. But there’s a cost we rarely discuss: the more abstract our lives become, the more disconnected we feel. Not just metaphorically disconnected. But experientially disconnected. Quite literally disconnected from the felt sense of being alive.

In Week 1, we explored how the Agricultural Revolution created the first major shift: when seeds went into the ground, our minds went into the future. For the first time, survival required living months ahead of ourselves.

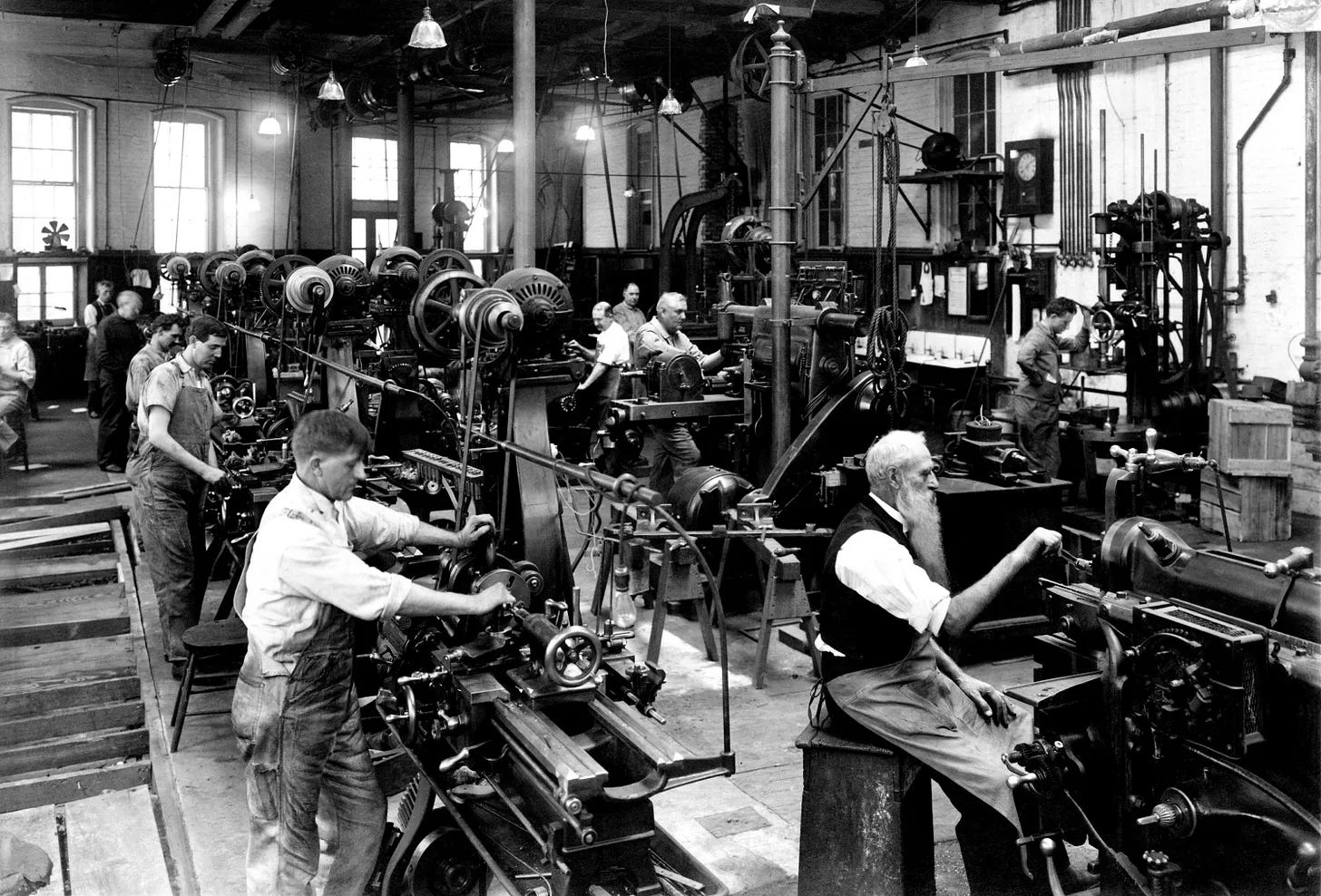

In Week 2, we traced how the Industrial Revolution severed three fundamental connections: from embodied work (machines did the making, we just tended them), from natural environments (permanent urban life), and from local information (newspapers brought distant abstractions into daily thought).

Each rung didn’t just add more abstraction. Each rung compounded it. Made presence harder. Made the felt sense of being here more difficult to access.

And here’s what is becoming increasingly clear: Most people never fully experience the alternative. Not really. Not fully. Not as their default state.

There’s a way of being fully present—sensory-rich, embodied, grounded, alive—that research is starting to show was the baseline human experience for 95% of our species’ history. Not a mystical or spiritual state achieved through decades of meditation practice. A default mode of cognition that immediate-return environments naturally produced.

We’ve been climbing away from that baseline for 10,000 years. And the Digital Revolution?

That’s when we started sprinting up the ladder.

That’s a quick recap. Let’s begin this week’s article.

When Reality Moved Behind Screens

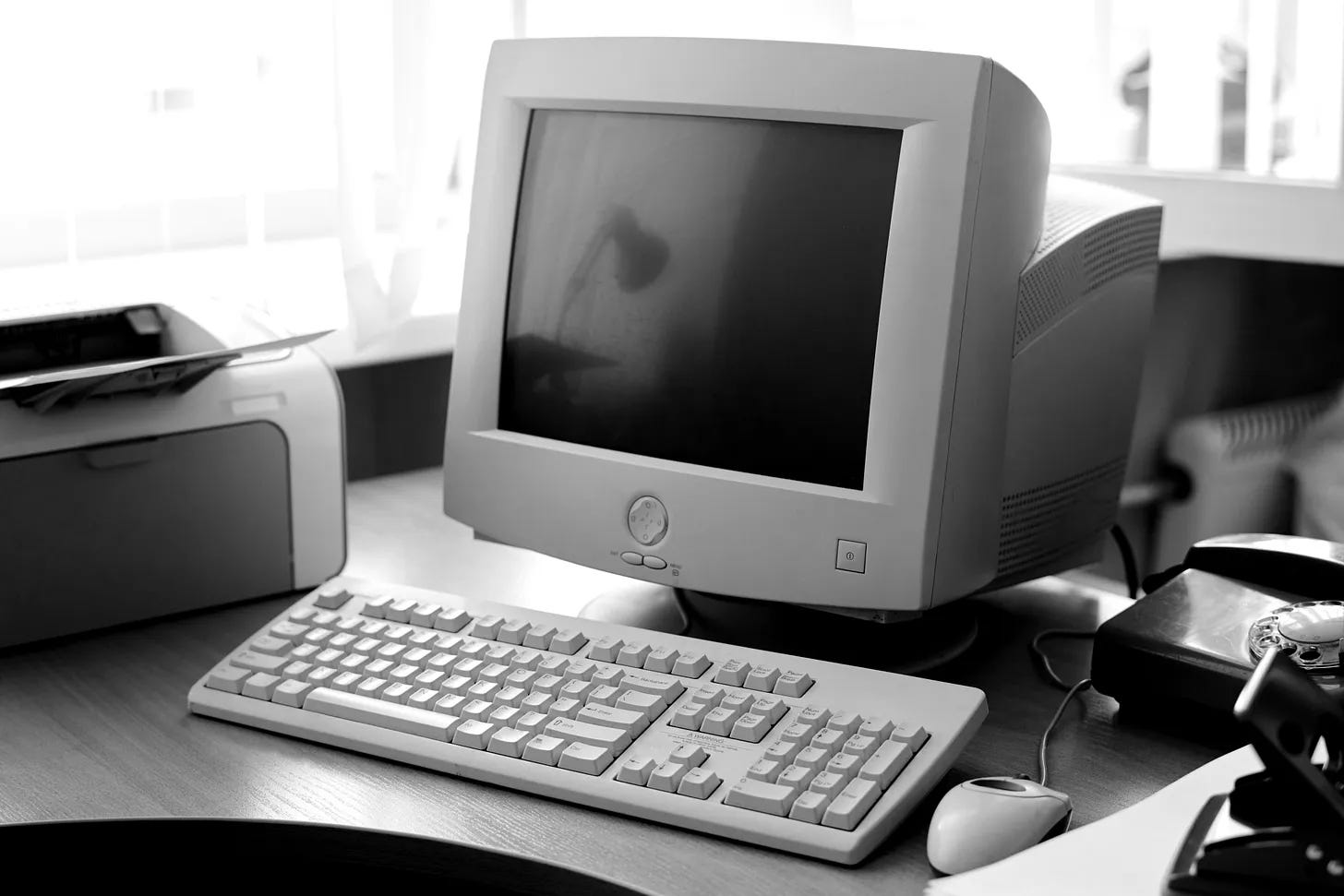

Remember the factory worker from last week? The one who left the farm for mechanical work. His great great great granddaughter is sitting at a desk in 1995.

There’s a beige box on that desk. A screen. A keyboard. A “mouse”.

Computers just arrived in the office.

She’s always been a quick learner, and very quickly adapts to pressing keys on the board and making incredibly accurate clicks with the mouse.

She types. Numbers change on the screen. Somewhere, something happens. She doesn’t know what. She doesn’t need to know what. The system handles it.

This is her job now: manipulating symbols that represent other symbols that represent things happening in databases she’ll never see, processed by servers in buildings she’ll never visit, affecting outcomes she’ll never directly observe.

Her body does essentially nothing. Her hands move slightly. Her eyes track pixels. But her mind—her mind is doing something unprecedented in human history.

She’s operating entirely within a symbolic layer that has no real physical form, no sensory feedback, no embodied reality whatsoever.

Her great great great grandfather in the factory at least pulled levers that moved gears that shaped metal that he could see. He still moved. There was still something physical happening.

But this? This is pure abstraction.

And it’s, quite unintentionally, about to become the dominant interface through which humans experience reality itself.

Reality Becomes Optional

The Digital Revolution didn’t just add another layer of abstraction. It created something fundamentally new: a parallel reality made entirely of symbols, accessible only through screens, that increasingly replaced direct experience as the primary way we navigate the world.

Think about what this actually means:

Information divorced from matter. For 300,000 years, information came through direct sensory experience or from people physically present. Even with writing and newspapers, information still required physical form—paper, ink, a person delivering it. But digital information? It has no physical form. It exists as electrical states in silicon.

Everything mediated through interfaces. You don’t go to a place and browse physical objects anymore. You scroll through representations of products. You don’t have conversations, you exchange text messages. You don’t fully experience moments or their memories, you take photos that you’ll review later on a screen rather than actually being present for the moment itself. The screen becomes the primary interface. And screens show you representations, not reality. Symbols, not substance.

The collapse of physical boundaries. You can work from anywhere. Shop from anywhere. Consume media from anywhere. Your “location” becomes almost meaningless in a way that would have been incomprehensible to your ancestors.

But here’s what nobody warned us about: when you can be anywhere, you’re never fully here.

Your body is in one place. Your attention is in dozens of others simultaneously. Email from a colleague. News from another continent. A text from a friend. A notification about something that happened somewhere else. Social media showing you fragments of other people’s lives.

You’re physically in your living room, but cognitively you’re nowhere. Or everywhere. Which amounts to the same thing: not here.

Presence Becomes Impossible

And then came social media. And then came smartphones.

Suddenly the parallel reality wasn’t something you accessed for specific tasks. It was always there. Always accessible. Always pulling.

The Harvard study I mentioned in the original article found that people spend 47% of their waking hours thinking about something other than what they’re currently doing. That study was from 2010—the iPhone had been out for three years, Facebook was still mostly desktop-based, Instagram didn’t exist yet.

Imagine what that number is now.

But here’s what makes the Digital Revolution qualitatively different from what came before: it’s designed to prevent presence.

Agriculture didn’t try to pull your mind into the future—that was an unavoidable consequence of delayed feedback. The factory didn’t try to disconnect your body from outcomes—that was a side effect of mechanization.

But your phone? Your apps?

Many are explicitly engineered to keep you in abstraction. Not just to capture your attention—that’s what everyone talks about, the “attention economy,” the “distraction crisis.” That’s real, but it misses something deeper.

The real mechanism is this: these systems are designed to keep you living in your head, processing information about things rather than experiencing things directly.

Every notification is an invitation to leave the present moment and enter abstract thought. Every scroll is moving through representations—of other people’s lives, of events elsewhere, of things that aren’t here. Of other things that aren’t even real. Every feed is a stream of symbolic information that pulls you out of sensory, embodied, here-and-now experience and into abstract, conceptual, somewhere-else processing.

This is the ladder of abstraction made algorithmic. Made compulsive. Made inescapable.

You’re not just distracted. You’re being systematically pulled up the ladder, rung by rung, dozens of times per hour, until living in abstraction becomes your default mode and presence becomes the exception you have to fight for.

Connections Become Superficial

But perhaps the deepest abstraction is social.

For 95% of human history, your social world consisted of perhaps 50-150 people you knew intimately. Face to face. Bodies in space. Direct, unmediated social feedback.

Now? You’re comparing yourself to thousands, no, millions. You’re processing information about people you’ll never meet. You’re maintaining relationships through text that removes tone, body language, presence, all the embodied social intelligence that evolved over millions of years.

Even when you’re with people physically, the phone is there. The screen is there. You’re together, but not present together.

Research on this is clear:

Phubbing (phone snubbing) measurably degrades relationship quality and satisfaction

Mere presence of a phone on the table reduces conversation quality and perceived empathy

Social media use correlates with increased loneliness, anxiety, and depression—especially in young people who’ve never known anything else

But here’s the deeper mechanism: digital social interaction is inherently abstract social interaction.

You’re not reading emotional states from faces and bodies. You’re interpreting symbols—text, emojis, images carefully curated and filtered. You’re not in the immediate feedback loop of eye contact and physical presence. You’re in a delayed, mediated, symbolic exchange.

And your brain—built for immediate social feedback over millions of years—experiences this as fundamentally unsatisfying. Incomplete. Unsafe, even.

That anxiety you feel scrolling social media? That sense of comparison and inadequacy? That compulsive checking?

That’s not personal weakness. That’s your brain trying to extract immediate-return social feedback from a system explicitly designed to provide delayed-return symbolic substitutes. Good luck!

And the cognitive costs of this are becoming quite clear:

The Kaplans’ Attention Restoration Theory demonstrates that modern environments—especially digital environments—create chronic directed attention fatigue. Your ability to focus, to be present, to resist distraction becomes progressively depleted.

Generalized Unsafety Theory of Stress (GUTS) explains why screens feel vaguely stressful even when the content isn’t threatening: your nervous system reads the absence of natural cues and embodied social interaction as potential danger.

The Default Mode Network research shows that when your mind isn’t actively focused, it defaults to abstract thinking—planning, worrying, ruminating, self-referential thought. The kind of thinking that makes you feel disconnected and anxious. Natural environments quiet this network. Embodied activities quiet it. Direct and authentic social interaction quiets it. Screens activate it. Constantly.

And here’s what really disturbs me, I honestly find it quite sad:

Most people will never experience what their mind was naturally wired for. A kind of effortless, embodied, grounded presence and deep sense of aliveness.

We assume that the modern experience is the default, the “normal” experience of being human. It’s not.

That meditation retreat where you finally felt present? That’s not you achieving some special state. That’s you briefly returning to the baseline cognitive mode that was standard for humans until very, very recently.

That hike where your mind finally quieted? That’s not relaxation. That’s your nervous system recognizing the environment it evolved for and dropping out of defensive abstraction.

That conversation where you locked eyes with someone and felt truly seen? That’s not intimacy as an achievement. That’s the immediate-return social feedback your brain has been desperately missing.

The thing you spend years and thousands of dollars chasing through practices and retreats and therapy?

It used to be our default state.

The Compounding Continues

Remember: abstraction compounds.

Rung 1 (Agriculture): Mind in the future

Rung 2 (Industrialization): Mind in the future + body disconnected + environment artificial + information distant

Rung 3 (Digital): All of the above + reality itself optional + social interaction abstracted + attention architecturally hijacked + presence almost impossible

Each layer makes the previous layers worse. The digital layer doesn’t just add more abstraction. It makes it harder to climb back down — even if you know you are up the ladder in the first place! (And most people don’t know. That’s the whole point of this series.)

Your phone makes it harder to be present at work. Harder to connect with nature. Harder to have embodied social experiences. Harder to get immediate feedback about whether your life is actually going well because you’re constantly comparing yourself to curated representations of other people’s lives.

And so the factory worker’s great great great granddaughter sits at that desk. Types symbols that affect things she can’t see. Eventually orders an iPhone. Scrolls through lives that aren’t hers. Reads news about events she can’t influence.

Her body barely moves. Her mind is everywhere and nowhere.

And at the end of the day, she feels... disconnected. Exhausted. Vaguely anxious about things she can’t name.

This isn’t personal failure. This is a nervous system built for immediate-return living, forced to operate in the most extreme delayed-return, abstracted, mediated environment in human history.

One More Rung

And we’re not done.

Next week, we climb to the fourth rung: The AI Revolution, when thinking itself becomes externalized.

What happens when the last distinctly human capability—abstract reasoning itself—gets abstracted into systems we can’t fully understand or control?

What happens when we outsource cognition the same way we outsourced craft?

I don’t know. Know one really knows. But we’ll explore it.

Because that’s where this story is heading. That’s where we are right now, in real time. At the start of the intelligence revolution.

But understanding how we got here—seeing the full ladder, each rung, each compounding severance—that’s the necessary first step. The first step to restoring what once came naturally.

You can’t address what you can’t see.

And what the Digital Revolution made clear is this: We have abstracted our experience of reality itself.

See you next week for the final rung.

Then next month we’ll explore how we can climb back down the ladder of abstraction and touch the ground.

—James

Note on AI collaboration: The ALIVE Letter explores how we can stay fully human while learning to work with modern technology. In that same spirit, I collaborate with AI in the creation of these articles. As an industrial/organizational psychologist who studies human-AI collaboration, I carefully guide, refine, and evaluate AI outputs. At its best, this partnership helps me more clearly and authentically communicate my own thoughts and perspective than I am able to alone.

Excited for next week! Even if that’s abstract :p