The Invisible Mechanism

How every technology asks us to live more and more in our heads

Right now, as you read this, something is happening in your mind that you can’t directly observe.

You’re not looking at ink on paper or pixels on a screen. You’re looking at meaning. Your brain is taking symbols—shapes, really—and converting them into thoughts, ideas, concepts. You’re experiencing something that isn’t physically here. You’re inside a representation of reality, not reality itself.

This is so ordinary, so constant, that it’s invisible. In fact, it’s automatic. Try this: look at the word below and try to see it as just shapes. Just lines and curves.

TREE

You can’t. Your brain won’t let you. The moment you see those letters, you experience tree—the concept, the meaning, maybe even an image. Psychologists call this the Stroop effect. Once you learn to read, you can’t not read. You can’t look at a word without immediately layering meaning onto it, filtering the raw sensory input through your conceptual understanding.

You’re always one step removed from direct experience. Always inside the abstraction.

So what is abstraction, exactly?

At its core, abstraction is the ability to create and manipulate mental representations of things that aren’t physically present. It’s thinking about what isn’t here. What isn’t now. What might never be.

When you plan tomorrow’s meeting, you’re running a simulation of a future that doesn’t exist yet. When you remember last summer, you’re reconstructing an experience that’s no longer happening. When you read the word “justice,” you’re grasping a concept that has no physical form.

This is different from the kind of thinking other animals do. A dog can learn. A crow can solve problems. But humans can imagine scenarios that have never occurred, reason about abstract concepts like democracy or infinity, and communicate about events separated by centuries.

We don’t just think. We build models—of the world, of other minds, of possible futures—and then we live inside those models.

This cognitive achievement is our superpower. It’s how we went from small bands of hunter-gatherers to a species that reshaped the entire planet.

But it comes with a cost that most of us never notice.

There are moments when abstraction stops.

You know this feeling, even if you’ve never named it.

You’re walking, or laughing, or dancing, and suddenly thinking stops. You’re not planning the next move or analyzing your performance. You’re just... there. Completely present. Body and mind unified in action.

Or you’re watching the sunrise, and for a moment—just a moment—you’re not thinking about the sunrise. You’re not comparing it to other sunrises or pulling out your phone to photograph it or planning what you’ll say about it later. You’re simply experiencing light and color and space.

This is what it feels like to be in direct contact with reality rather than living inside a representation of it.

The difference is palpable. One feels alive. The other feels... abstract.

The problem is, these moments are rare. And getting rarer.

In 2010, Harvard psychologists Matthew Killingsworth and Daniel Gilbert wanted to know how much time people actually spend present versus lost in thought.

They built an iPhone app that pinged 2,250 people at random intervals throughout their days, asking: What are you doing? What are you thinking about? How happy are you?

The results were striking.

People spent 46.9% of their waking hours thinking about something other than what they were currently doing. Almost half our lives, we’re somewhere else mentally.

And here’s what matters: mind-wandering made people unhappy. Not just during unpleasant activities—during everything. People were happier making love, exercising, or talking with friends when they were actually present for those activities, rather than thinking about something else.

The researchers found that what you’re doing matters far less than whether you’re mentally present while doing it.

Their conclusion: “The ability to think about what is not happening is a cognitive achievement that comes at an emotional cost.”

This cognitive achievement has a name: abstraction.

And here’s what almost nobody realizes: we’re doing more of it than ever before in human history.

Every major technological revolution hasn’t just enabled more abstraction—it has required it.

Agriculture demanded that humans learn to live in the future. You plant seeds in spring for a harvest in fall. You store grain for winter. You plan across seasons. Hunter-gatherers could live in the immediate present—tracking animals, gathering plants, responding to what’s here now. Farmers had to constantly simulate futures that didn’t exist yet and make decisions based on those simulations.

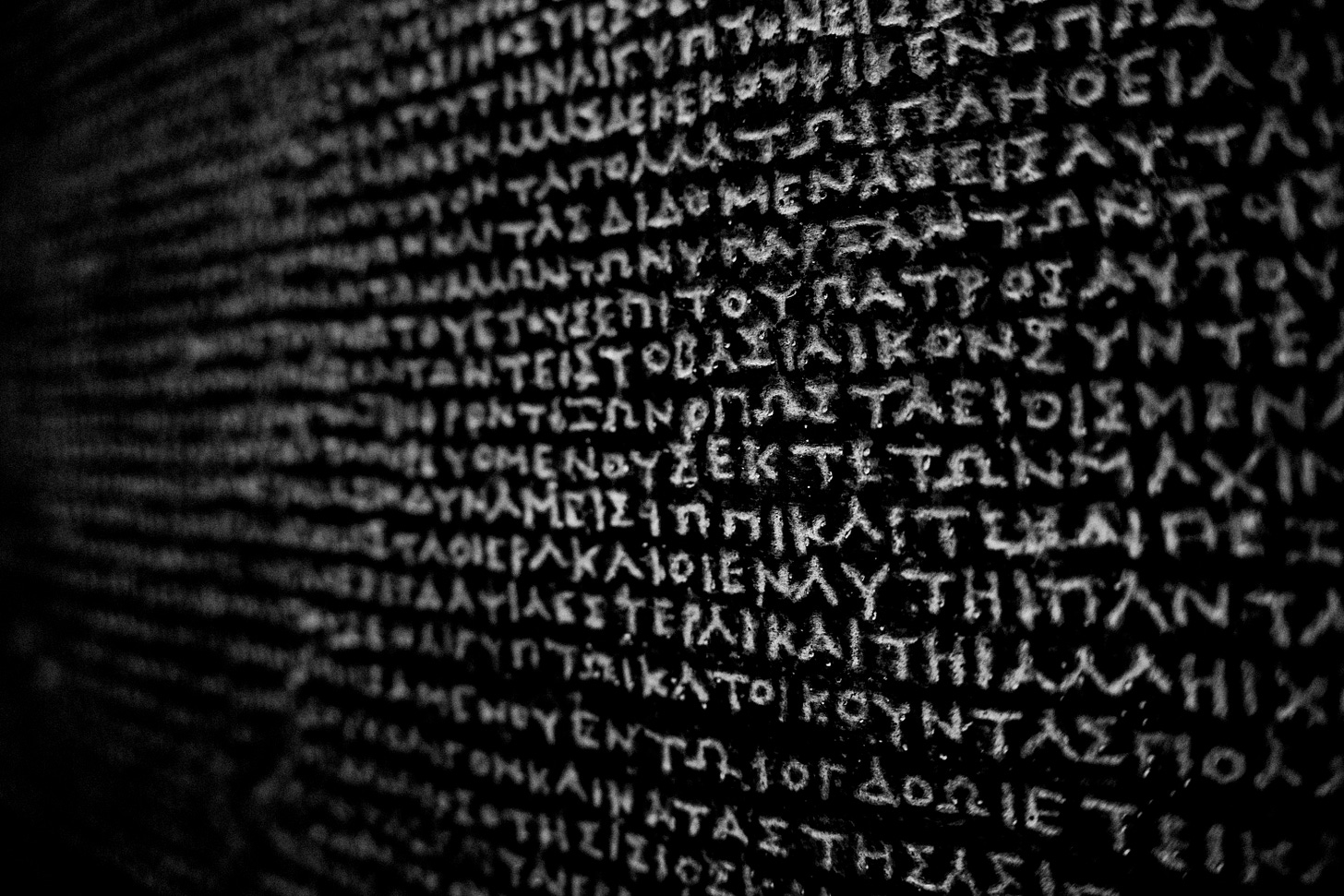

Writing severed knowledge from lived experience. For the first time, you could learn about places you’d never been, people you’d never met, events that happened before you were born. Knowledge became abstract—encoded in symbols rather than embedded in direct experience and oral tradition.

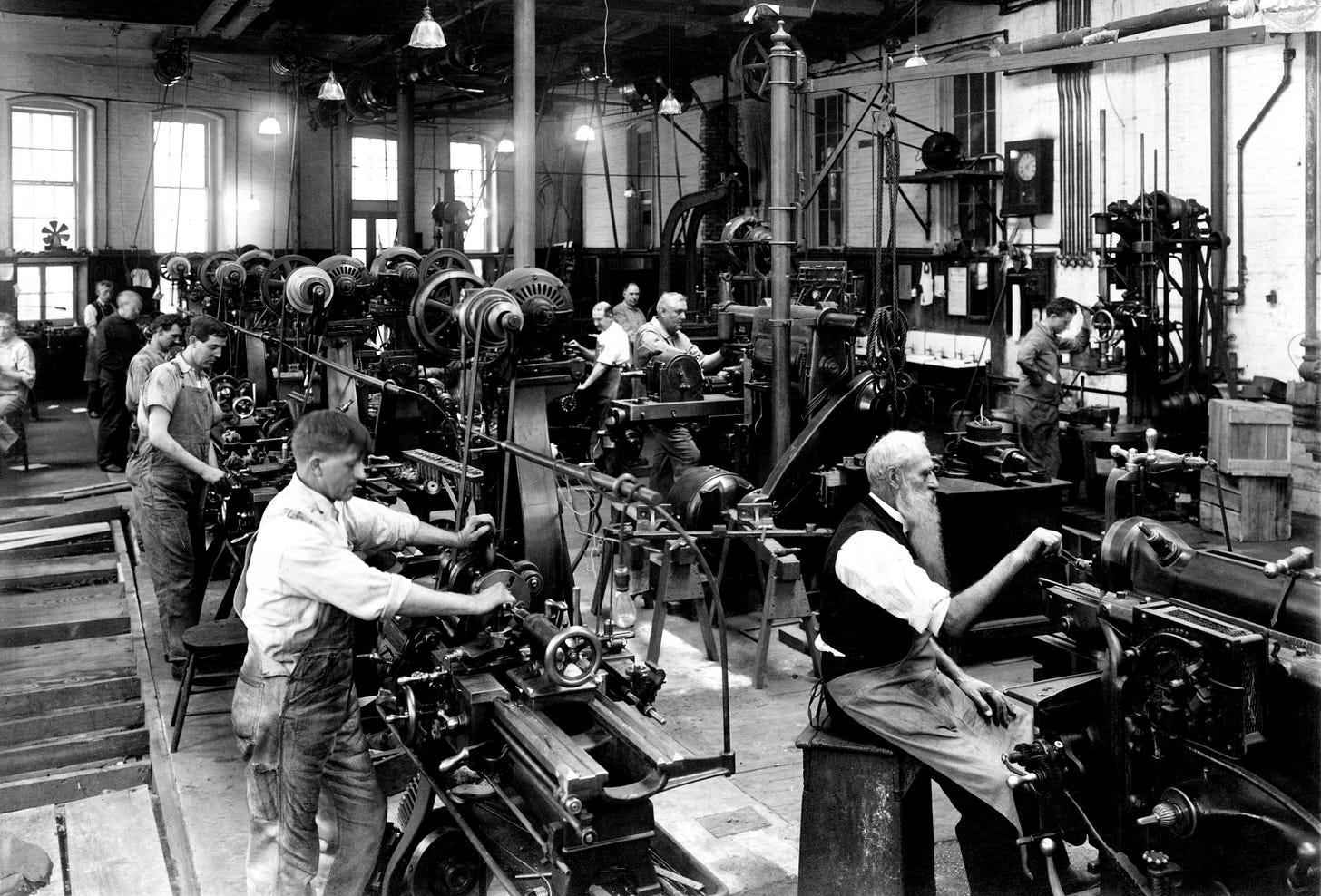

Industrialization broke the connection between work and outcome. A craftsman shapes raw material into a finished product with their hands. A factory worker pulls a lever that activates a machine that produces one component of something they’ll never see completed. Work became a series of abstract transactions—time for money, gestures for products made elsewhere by others.

The digital age put almost everything behind screens. You tap glass and things happen in server farms thousands of miles away. You don’t mail letters; you send packets of data through infrastructure you can’t see to people you might never meet in person. Reality became a set of interfaces, menus, and symbols representing actions that occur somewhere else.

And now, artificial intelligence is abstracting thinking itself.

The one thing we thought was irreducibly human—reasoning, analysis, even creativity—is being externalized into systems we can’t fully understand. We’re asking machines to do our cognitive work, which means we’re one more step removed from direct engagement with problems and ideas.

Each revolution made us more powerful. More capable. More able to shape the world.

But each also required us to spend more time in our heads, manipulating representations, living in simulations of reality rather than reality itself.

Starting next Wednesday, I’m publishing a four-part series exploring this trajectory in depth.

Each article will examine one technological revolution and how it fundamentally changed our relationship with abstraction:

Week 1 (Nov 6): The Agricultural Revolution — When humans learned to live in the future

Week 2 (Nov 13): The Industrial Revolution — When work became abstract

Week 3 (Nov 20): The Digital Revolution — When reality moved behind screens

Week 4 (Nov 27): The AI Revolution — When thinking itself became external

At the end of November, I’ll release a white paper synthesizing the key insights, patterns, and implications.

This isn’t about resisting technology. I study and build AI systems for a living.

This is about understanding the trade-offs we’re making—often without realizing we’re making them.

Because here’s what we’re losing:

The felt sense of being here. The texture of direct experience. The aliveness that comes from being fully present in your body, in this moment, in contact with reality as it actually is rather than as you’re thinking about it.

We’re living more and more of our lives inside our heads—planning, analyzing, remembering, worrying, scrolling through representations of other people’s lives. We’re becoming extraordinarily capable at manipulating abstract symbols and models.

But we’re forgetting what it feels like to simply be alive.

Not thinking about being alive. Not optimizing for aliveness. Not reading articles about presence.

Actually alive. Here. Now. In a body that moves and feels and senses the world directly.

That’s what’s at stake. And that’s the question at the heart of The ALIVE Institute’s mission: How do we stay fully human—embodied, present, alive—in an increasingly abstract world?

We can’t go back. We won’t go back.

But we need to understand what we’re trading. And we need to make that trade consciously, deliberately, with full awareness of the cost.

That’s what this series is about.

If you’re interested, I’ll see you Wednesday.

James